Before Kent Nerburn became an author, he was a wood sculptor. He changed his career after being hired in northern Minnesota to help high school students conduct a two-year oral history project interviewing Red Lake Ojibwe elders in 1988.

“I soon realized that I was in the presence of a way of living and believing that had a depth unlike any I had experienced in my typical American way of growing up,” Nerburn said. “And it was a way that perfectly fit my hunger for a spirituality that honored the mystery and life, but did not demand exclusivity or divide people between insiders and outsiders.”

After being struck by the suppressed history and worldview the Ojibwe elders described, he has written 17 books on the Ojibwe, Lakota and Nez Perce tribes. Nerburn’s lecture, “Quiet Voices, Important Truths: Life Lessons from the Native Way,” was released at 2 p.m. EDT Wednesday, Aug. 12, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform.

Nerburn recorded his lecture from his Oregon home, as part of Week Seven’s Interfaith Lecture Series theme, “The Spirituality of Us.” He reflected on his career switch and lessons he has learned from listening to and writing about Native American history, culture and spirituality.

When Nerburn was still a wood sculptor, he felt almost guilty for carving his ideas into trees. To him, it felt like he was imposing ideas onto something with a living soul. And for many Native Americans, there is a life force in trees. Nerburn said the Iroquois have carved masks from live trees so the spirit of the tree is imbued in the mask. Some tribes on the northwest coast of British Columbia carve faces in trees and then let the faces change as the tree grows.

Nerburn’s work collecting and sharing Native stories for the past 30 years isn’t done, which means he’s not done learning, either.

“There are so many stories I could tell, and so many stories I am still learning,” Nerburn said.

He first came across the work of Native philosophers and leaders while working with the Ojibwe students in 1988. He quoted Dakota philosopher Ohiyesa, also known as Charles Eastman:

“We have always preferred to believe that the spirit of God is not breathed into humans alone, but that the whole created universe shares in the immortal perfection of its maker,” Eastman wrote. “We believe that the spirit pervades all creation and that every creature possesses a soul of some degree, though not necessarily a soul conscious of itself. … We see no need for the setting apart of one day and seven as a holy day. For to us, all days belong to God.”

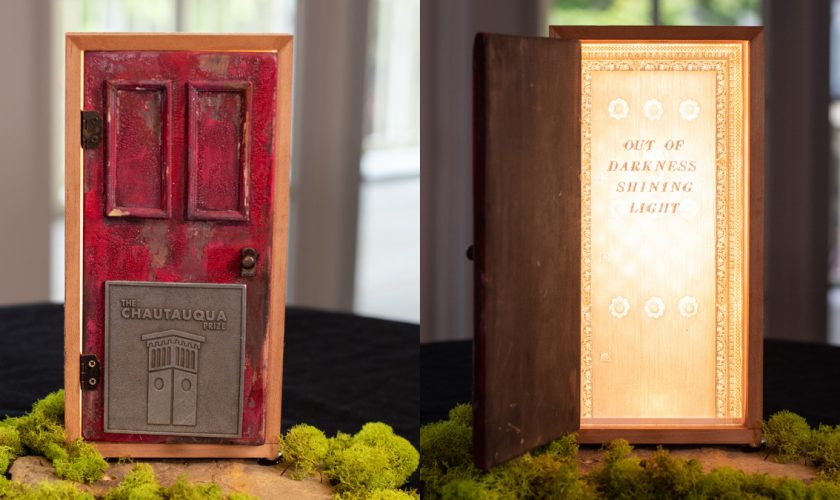

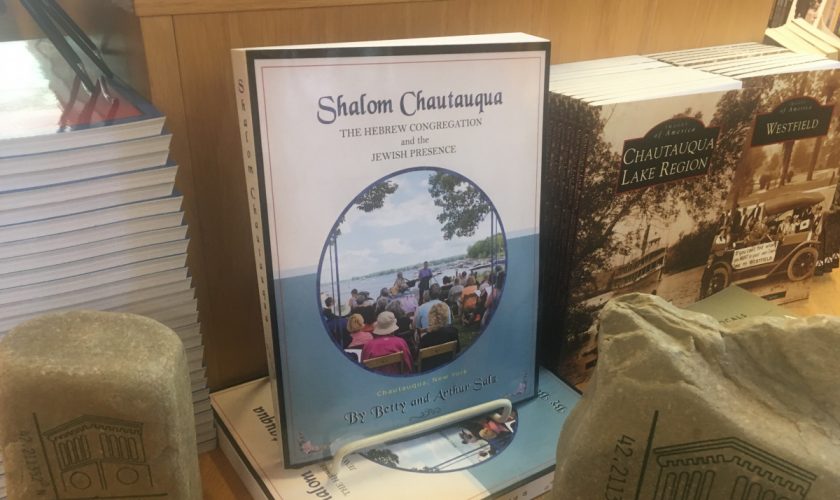

Nerburn found his purpose in listening to and sharing the stories and lessons from Native people, opening a door for the rest of the world to learn with him from Native American perspectives and life lessons he details in his work. In his lecture, he read two sections from his book Voices in the Stones: Life Lessons from the Native Way.

In one section, “Stones for the Sweat: All People Should Be Made to Feel Needed,” he described a Nez Perce man’s account of his ancestor Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph. The man also described responsibilities for children and elders when he was a child. While children were tasked with braiding horse bridles, elders made community decisions based on their breadth of life experiences.

“It granted them an unassailable status and responsibility that belonged to them and no one else,” Nerburn read.

In the second section, “The Old Man in the Café: Spirit is Present in All of Creation,” Nerburn described his chance encounter in a café with a Native man who in his youth had been forcibly sent to the Fort Totten Indian Boarding School, which Nerburn was researching at the time. The U.S. government created schools like Fort Totten to forcibly assimilate Native American children.

“I learned Good English,” the man said to Nerburn. “I learned Good Christian. But I am no longer myself.”

Children who were initially taught to learn from their elders were forced into these schools to learn the ways of the dominant U.S. culture and Christian religion. White teachers told children that their elders would go to hell for their beliefs.

“This man, for all his class and manner and sanguine outlook, was the very embodiment of what we as a nation had done to the Native peoples, who had stood in our path as we pushed our way across the continent,” Nerburn read.

Part of Nerburn’s work requires him to unwind the United States’ systemic damage done to Native Americans and Native values. In his research, Nerburn found out a government leader in charge of Native training and education in the 1870s had said that the Indians need to learn the “exalted egotism of America” — in other words, to think of “I” rather than “we.”

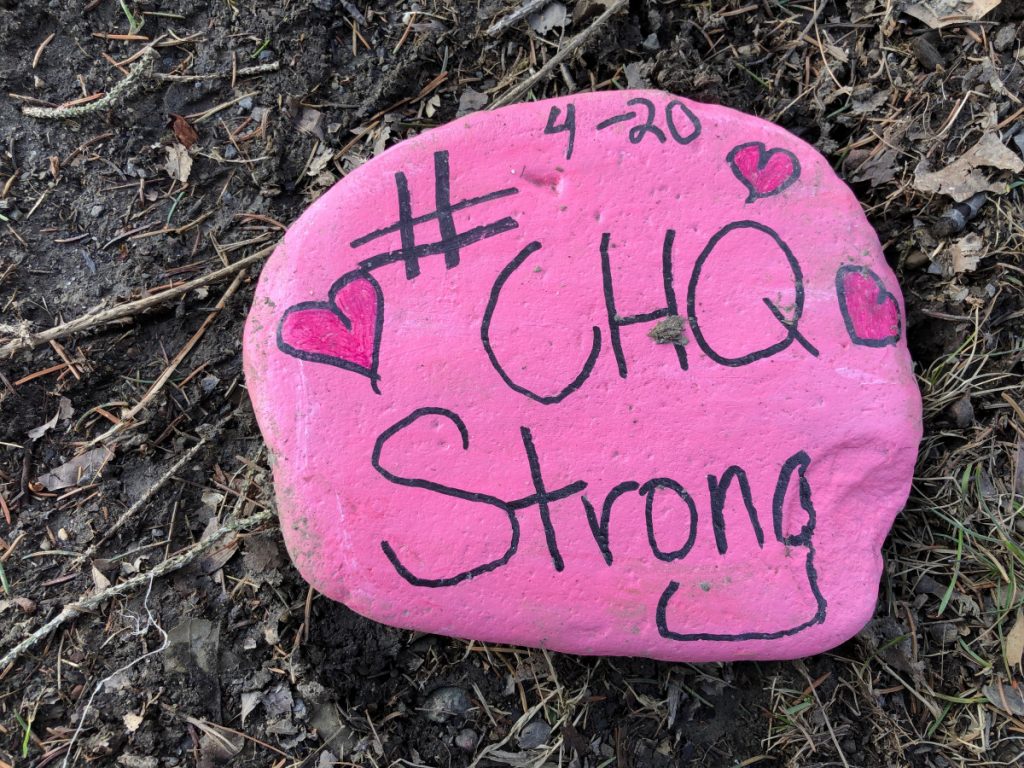

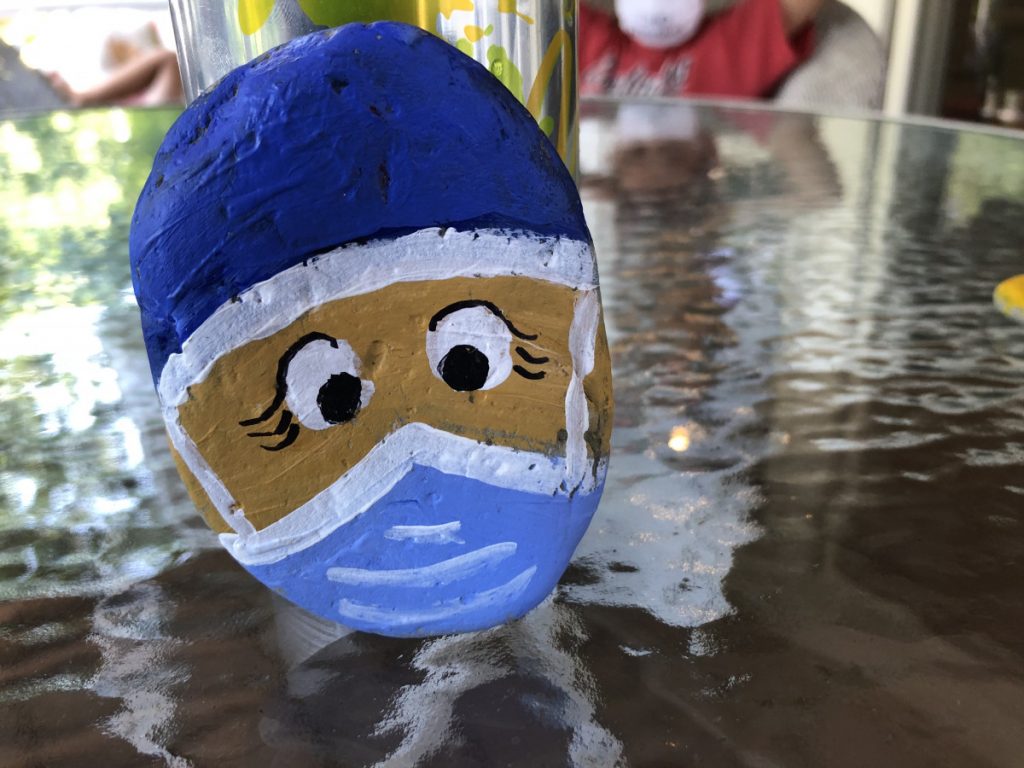

Nerburn said that while Native Americans have worked to uphold this value of “we,” the rest of the United States has yet to learn this, especially in light of some people who refuse to wear masks or practice social distancing to prevent COVID-19 transmission.

Nerburn sees an opportunity during the pandemic for everyone to reconsider societal priorities and values; to look out for group needs rather than individual needs.

“Every child in America right now is being influenced by (the pandemic),” Nerburn said. “When we get through this — if we don’t sacrifice them all on the altar of normality by sending them back to school or putting them in bad situations — every kid in the world that went through this will have something in common with every other kid. And as their time comes, they’ll remember that and look at themselves as part of the human family.”

Nerburn’s work calls people to pay attention and listen to Native stories. After speaking with Native people for 30 years, there is one phrase that he’s heard over and over again: White people need to listen.

“The first thing we need to do is to stop controlling and start to listen,” Nerburn said. “And that takes away the sense of responsibility for mastery. I think that’s really the key to the Native way of understanding — to accept rather than to master.”